Bach's Extraordinary Transcriptive Powers

Sonata in a minor, BWV 965, After Johann Adam Reincken.

(This post is in conjunction with the following YouTube video I’ve just released where I perform the work in question. Subscribe to my YT to make the most of your Bachian habits!)

Sometime around 1714-1717, Bach made transcriptions from Hortus Musicus (1688) by the important North-German/Dutch master, Adam Reincken. Reincken and Buxtehude were apparently friends, and both were seminal in forming young J.S.’ style.

Hortus Musicus is written for two violins, viola da gamba and basso continuo. The pieces are sonatas (slow-fast-slow-fast) with suites at the end. Of the six pieces in the collection, Bach transcribes from three of them, giving us BWVs 954, 965 and 966.

Today’s work, BWV 965, the ‘a minor Sonata,’ is the only complete transcription: all movements included. BWV 966 is almost complete: the Courante, Sarabande and Gigue are missing. BWV 954 is a single movement: a fugue based on Reincken’s theme.

Compare the concerto transcriptions also made around this time, BWVs 972-987. Bach only occasionally alters the form of the original models— adding or subtracting a bar here or there. Mostly he retains the original structures. It’s really the embellishments where we learn— and indeed delight:

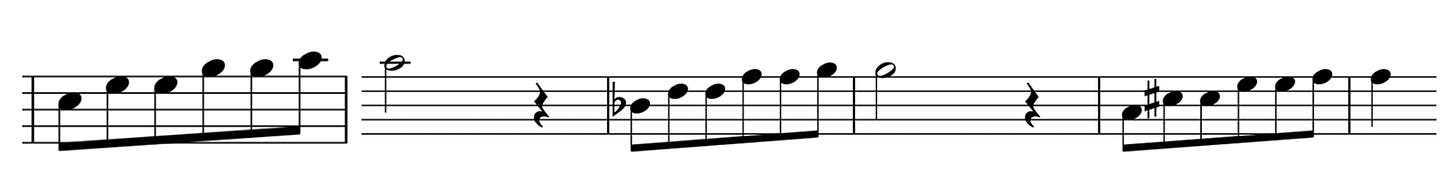

This unadorned passage from Marcello, for example:

Becomes Bach’s:

In the Reincken transcriptions, however, Bach not only gives his embellishments free rein, but whole movements have new structures. It’s as if we watch the young Bach acquiring mastery in stages: First, transcription with the form intact. Second, transcription with freer form. Third, original compositions.

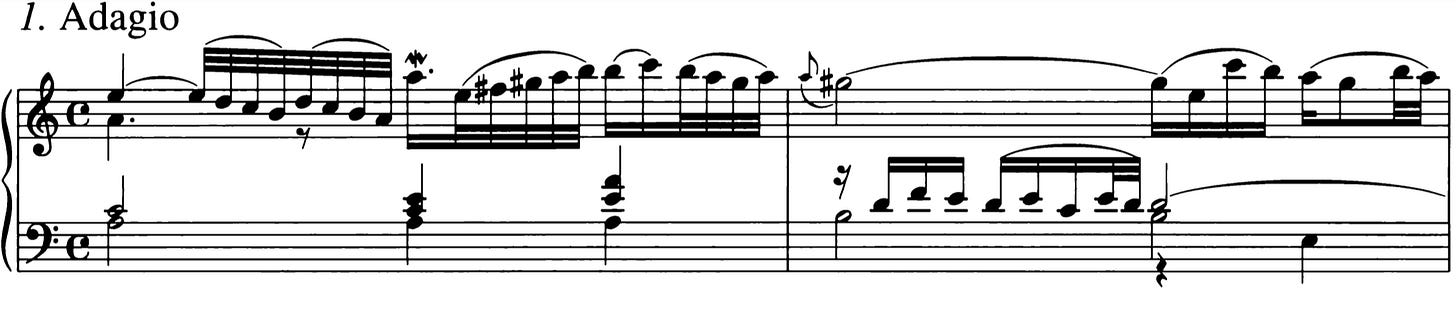

Let’s begin with the opening movement of BWV 965 to see some of this wonderful imagination. Bach’s piece begins:

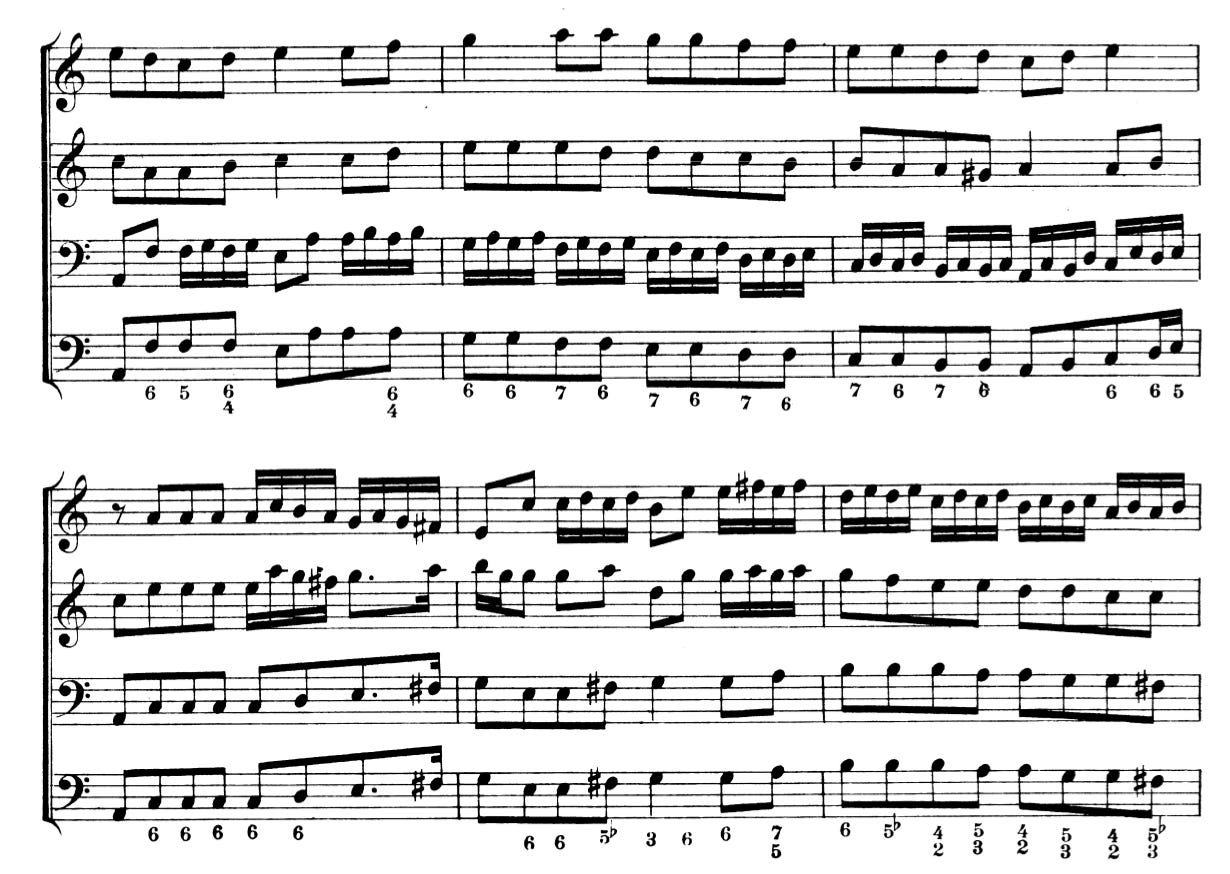

He squeezed that music from this, his model, the Reincken:

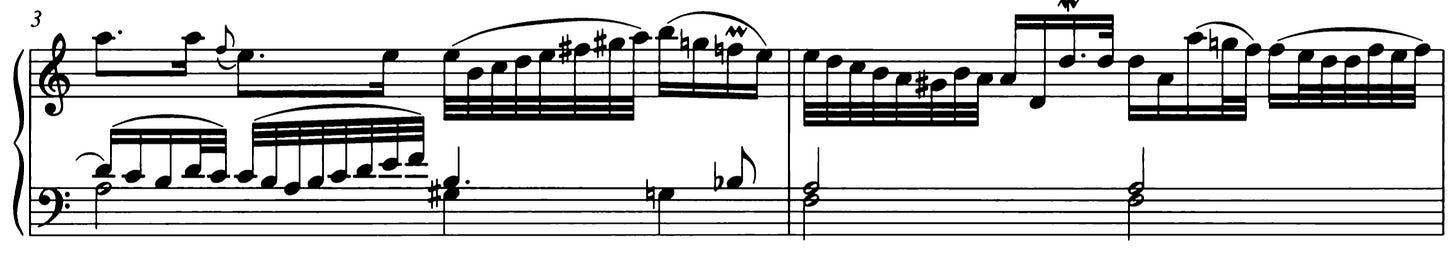

It may take a moment before you see that one is in fact a transcription of the other. These examples might be a lesson to us in improvisation. They probably provide clues into the performance practice of the times. See here, in bar 12, where Reincken gives us two chords:

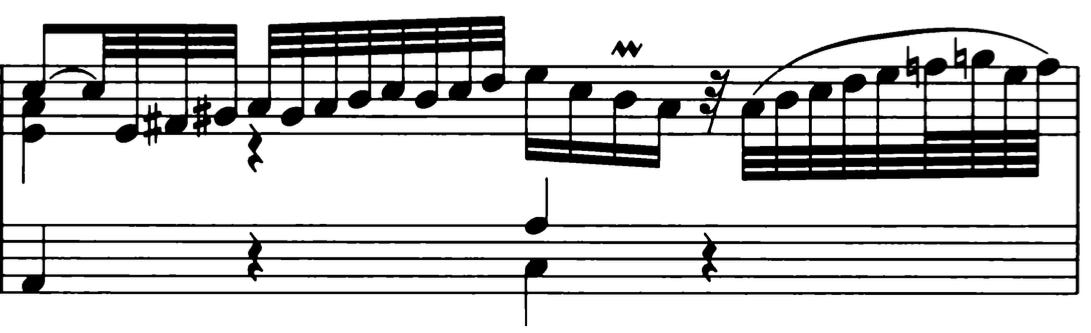

In 1688, It might have been ‘incorrect’ to play the notes unembellished. In any case, Bach’s interpretation sees fullness:

More examples from the opening movement. Bars 15-16 in Reincken:

Notice especially how Bach renders simple descending parallel 6ths:

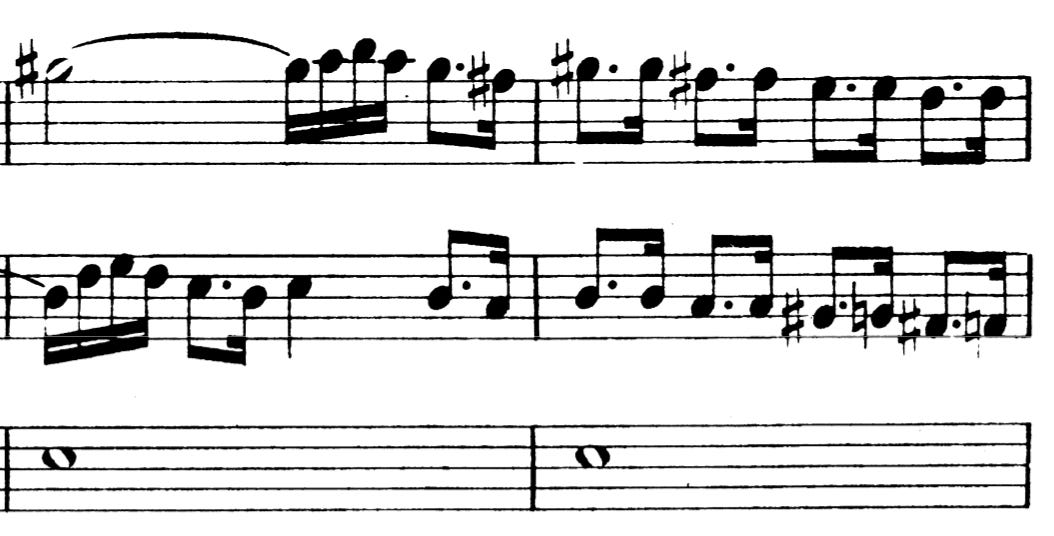

Onto the fugue. The fugues in BWVs 954, 965 and 966 might as well not be called transcriptions, but fugues based on themes by Reincken. Stylistically they remind us of his fugues on themes by Albinoni, BWV 949, BWV 950, BWV 951, BWV 951a, where only the theme and perhaps a few ‘gestures’ of the originals are preserved. Let’s take the exposition of Reincken’s as our starting point:

Bach will drop the basso continuo accompaniment, as one does in a solo keyboard fugue, but see what other differences you notice:

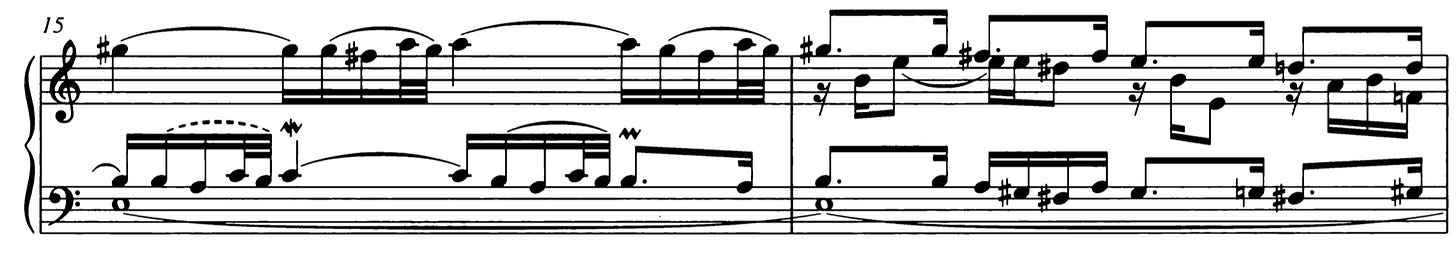

For one thing, Bach’s accompaniment is more active. Note the soprano while the alto enters in Reincken:

Bach:

Reincken’s fugue is 50 bars in length, Bach almost doubles this! Reincken omits episodic material: the themes coming immediately one after the other. The tonality doesn’t stray from alternating between tonic and dominant. Bach achieves his longer composition by impregnating the fugue with episodes and modulations to more distant tonalities. See here an episode plunging into distant keys, and an entrance in d minor. B-flats and E-flats, for example, will not be found in Reincken:

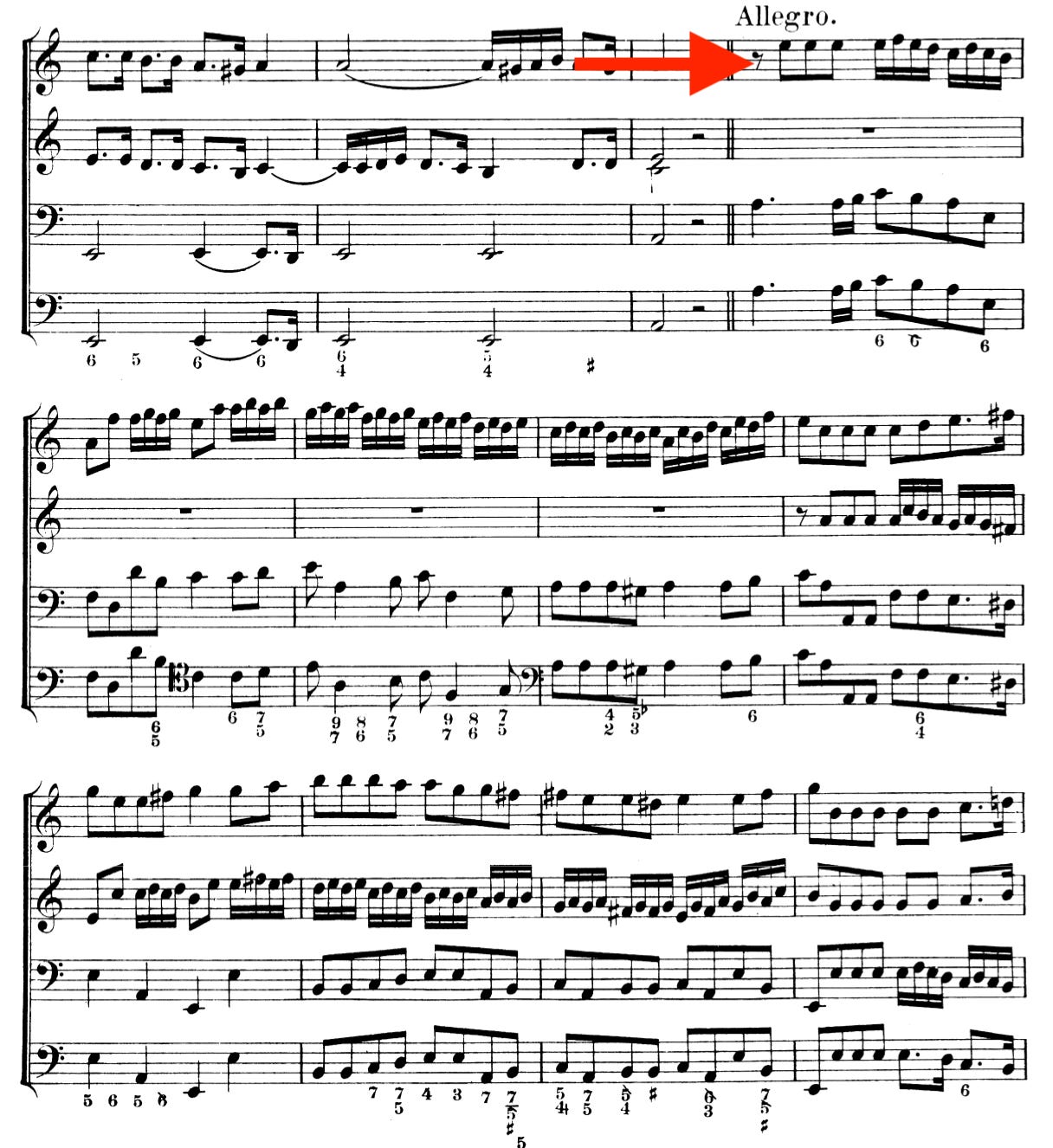

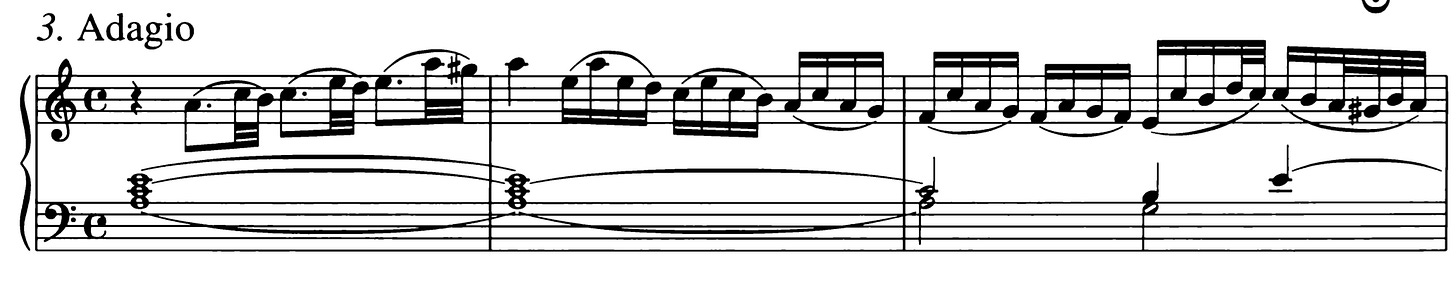

In the next movement (the last in this particular video,) rather than expanding the form, Bach truncates the original. Reincken’s idea is to showcase separate solo instruments playing similar passagework. First a look at Bach’s embellishments:

His model is again, a mere sketch. Note the transition to the presto:

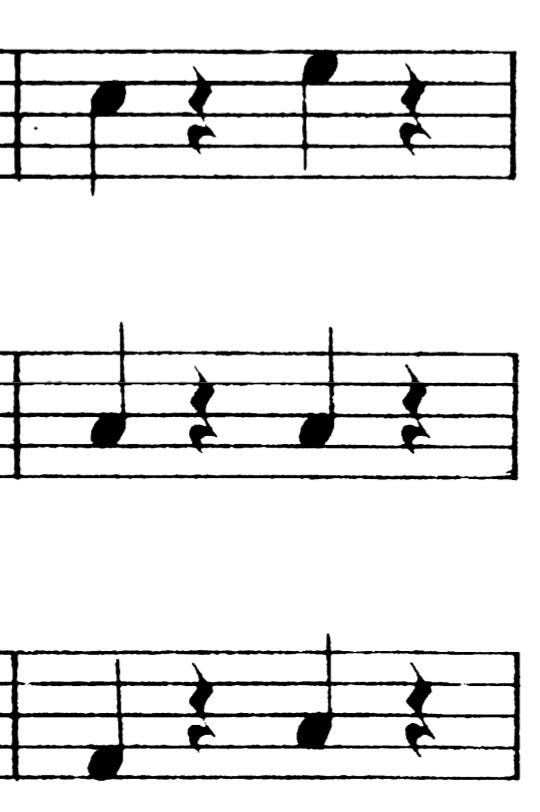

The presto goes on for 17 bars (dutifully preserved by Bach,) but then the viola picks up the idea:

The viola will then play another presto, but Bach, transcribing for a single solo instrument, will showcase the virtuosity only once. The first and only time through the passagework, the music comes to a double bar. Notice the harpsichord-like legato ‘stemming’ at bar 20:

It could be mentioned that Bach did not conceive these transcriptions as an ‘improvement.’ Reincken was from an older generation, so perhaps the more appropriate way to contextualize this is akin to Chopin writing variations on Mozart, or Coltrane playing Duke.

As for recordings of Reincken’s original, this one struck me as particularly nice. When listening to it, I think we can sense it as music belonging to a generation before Bach’s.

Enjoy! Thanks for watching. Thanks for reading.

-e.s.

Keep this resource alive! We Survive on your Donations! Thank you!

We encourage our listeners to become a paid subscriber at wtfbach.substack.com

You can also make a one-time donation here:

Supporting this show ensures its longevity!

—Help WTF Bach reach more listeners—

Concepts Covered:

Discover how a young J.S. Bach in transcription reimagined Adam Reincken’s Hortus Musicus, creating works like BWV 965, BWV 966, and BWV 954 that showcase fugal structures, bold ornamentation, and the art of Baroque improvisation. We deep dive into Bach’s process—how unornamented originals become richly embellished masterpieces, how simple fugue subjects grow into expansive contrapuntal designs, and how these transcriptions illuminate performance practice of the time. We explore Bach’s early genius, bridging the North-German Baroque tradition with his own voice.